With COVID raging, why are we even still playing college basketball?

Fortune,

It was public, shocking, and very real. In a game against rival Florida State on Saturday, the University of Florida basketball star Keyontae Johnson, just 21, collapsed facedown on the court, unconscious. He was removed by paramedics and taken to Tallahassee Memorial Hospital, where he was reported to be in critical, but stable condition. His Gators teammates, some in tears, huddled to pray, and after some discussion the game continued, with Florida State putting away a comparatively meaningless win.

While the cause of Johnson’s collapse was not immediately clear, one of the details that we already have is worrisome enough: Many members of the Florida team, including Johnson, tested positive for COVID-19 during the summer.

And while I’ll explain in a moment how those two events—the COVID diagnosis and Johnson’s medical emergency—might be related, we need to first step back and ask a much larger question: Given what we already know about the spread of the virus, why is the NCAA powering ahead with basketball at all?

Nationally, the pandemic continues to rage. We’re at roughly 200,000-plus daily cases, an increase of 30% over the past two weeks; 2,400 people are dying per day, up 67% for the same period. We know that hospitals around the country are getting slammed, with intensive care units (ICUs) nearing capacity. Staffing shortages are real, with health care workers falling ill or some even leaving the profession, and hospital providers are exhausted, pleading for help from the community to take the situation more seriously and stay home.

Anthony Fauci, the infectious disease expert leading our national COVID effort, the World Health Organization (WHO), the Centers For Disease Control (CDC)—all have recommended restricting large gatherings, prioritizing outdoor activities over indoor ones, and distancing six feet or more from those not living in your same household. They recommend limiting attendance at indoor training sessions, as well as wearing masks.

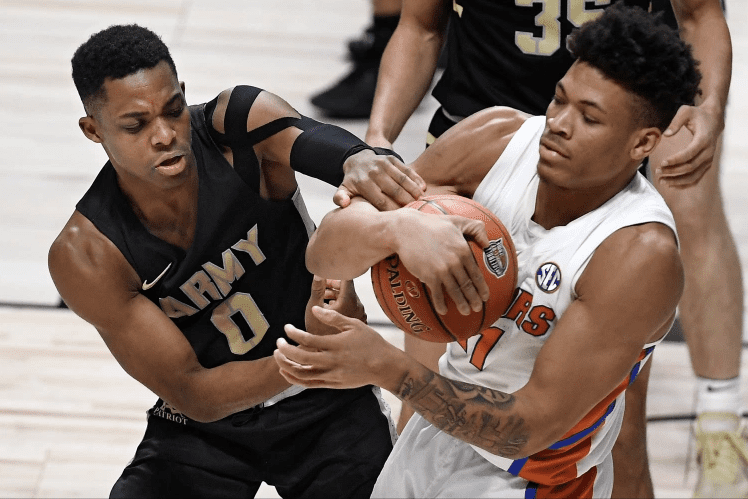

Playing basketball indoors pretty much flies in the face of all these recommendations. How much closer can you be to someone than when you’re right in their face guarding them, breathing heavily, running into one another, amid dripping or flying sweat? (Anyone who calls basketball a noncontact sport never played it at the higher levels.) Traveling to various cities, staying in hotels, visiting various schools and facilities, then returning back to your own college community—none of it makes sense medically, and it’s dangerous.

It’s almost as if the NCAA is not aware of COVID-19’s droplet and aerosol spread, which is frankly hard to believe. Time and again we have seen outbreaks occurring in indoor settings such as restaurants, bars, church services and weddings, etc. We understand now, too, that via aerosols, the coronavirus can spread at even greater distances—20 to 30 feet—and can linger in the air for minutes to hours, infecting others. Just last week, a study from Korea reported on a case of coronavirus transmission documented indoors after just five minutes of exposure without any direct contact—from 20 feet away.

“Indoor basketball increases the risk of COVID-19 in multiple and concerning ways,” said Lupita Montoya, an indoor air quality and aerosol expert at the University of Colorado. “The generation of aerosols from the players is increased by physical activity, and unabated by a mask.”

Is it any wonder that 15 to 20 college basketball coaches already have tested positive for COVID-19, or that multiple teams have players testing positive, or that there have been a slew of game cancellations? Keep in mind, the college season only began on Nov. 25th. Duke, USC, Florida A&M, George Mason, Towson, Baylor, the Connecticut women’s team, Utah, Wichita State, Tennessee, and many others have canceled games because of at least one player or staff member testing positive for the virus.

It prompts the question, why? Why are we playing college basketball, putting athletes and coaching staff at risk of a deadly virus? The NBA, with all of its protections and testing ability, still had 48 of 546 players test positive during the last week of November—almost 9%. (The pro league is not imposing the same “bubble” conditions that kept players and staff free of infection during the NBA playoffs earlier this year.) College players and teams, meanwhile, do not have the same resources as the pros. What will their positive-testing percentages turn out to be? And why take that risk?

The short answer is that there’s significant money involved. Basketball produces more than $1.1 billion for the NCAA in a normal year, which includes the March Madness tournament, a massive moneymaker for the organization. But just as that tournament was canceled last season, so should this entire 2020–21 schedule be reconsidered.

A troubling link

We have no idea at this point whether Keyontae Johnson’s collapse is related to COVID-19, or to something entirely different. But you can bet his physicians will be evaluating the COVID angle.

What we do know is that, speaking generally, there are multiple possible etiologies of a sudden loss of consciousness in athletes. The causes can range from something as benign as dehydration to much more serious health problems. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, a disease in which heart muscle becomes abnormally thick, is a common cause of cardiac death in competitive athletes. But another culprit in incidents like this is a heart condition that has been closely linked to COVID: myocarditis.

Myocarditis is a rare condition that generally is due to either an unknown cause (“idiopathic”) or a viral illness. It leads to inflammation of the heart muscle, which can affect its ability to pump. It is known to occur more commonly in males than in females, ages 20 to 40, and can result in serious arrhythmias, loss of consciousness, heart failure, and even sudden cardiac death.

According to some scientific reports, as many as 7% of deaths from COVID-19 may result from myocarditis. (Others feel that estimate is too high.) Arrhythmias have been found to be fairly common among COVID-19 patients.

In COVID patients, myocarditis appears to result from the direct infection of the virus attacking the heart, or possibly as a consequence of inflammation triggered by the body’s overly aggressive immune response. At autopsy, researchers have reported the presence of viral protein in the actual heart muscle of deceased patients—so viral involvement is possible, though the true etiology may be multifactorial.

According to reports, cases of myocarditis have been seen to occur both in patients during their acute COVID illness or hospital stay and in the many weeks or even months following infection—even in those who experience only mild or asymptomatic illness initially.

The true incidence of myocarditis developing in recovered COVID patients is not known. But one non–peer reviewed study, involving 139 health care workers who developed coronavirus infection and recovered, found that about 10 weeks after their initial symptoms, 37% of them were diagnosed with myocarditis or myopericarditis—and fewer than half of those showed symptoms at the time of their scans.

Similarly, a recent small study from Ohio State University reported on 26 COVID-positive male and female college athletes from a range of sports, all of whom had mild or asymptomatic COVID-19 while sick. Using cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans performed between 11 days and nearly two months from the athletes’ recommended quarantine, researchers found that 15% of the athletes (all males) had findings suggestive of myocarditis, and 30% showed changes consistent with prior injury to the heart. The Big Ten Conference, to which Ohio State belongs, reported that 35% of its COVID-positive athletes had myocarditis.

Statistically, most young people do quite well with coronavirus (though not everyone), but the long term is a concern here, too. We know of tragic cases like that of former Florida State basketball player Michael Ojo, who died of suspected heart complications just after recovering from a bout of COVID-19 in Serbia, where he was playing pro ball.

In college football, Indiana University offensive lineman Brady Feeney dealt with possible heart issues. University of Houston player Sedrick Williams opted out of the season because of “complications with my heart.” From both the college and pro sports ranks, there are many other stories like these.

And we haven’t even discussed the “long haulers,” people who experience worrisome symptoms for weeks or months after their initial illness: shortness of breath, fatigue, chest pain, relapsing fevers, “brain fog,” on and on. Some of these are young, healthy people who had mild or even asymptomatic initial COVID infections.

My son was a college athlete. I understand how hard these athletes train, how much they want to compete, and what great fun and joy the games bring to avid sports fans. I also know how important college athletics is to universities and their bottom lines, and how much is generated from television revenue. On so many levels, I get it, and I pray for Keyontae Johnson’s safe recovery. But one player dead is too many, and another pitching forward unconscious on the basketball court should prompt a complete reconsideration of what we’re doing here.

With the findings of myocarditis and other ailments in COVID-positive athletes, and the real potential of long-hauler symptoms in previously healthy young adults, it’s irresponsible to continue indoor sports at this point. We know enough now. Vaccines are on the way. Let’s postpone this season for six months in order to vaccinate players when the shots become available.

For the 2020–21 college basketball campaign, August Madness is clearly the way to go. It may not have the same ring to it. Then again, nothing about this pandemic is normal.